Visualizing the Bayesian workflow in R

Introduction

The following (briefly) illustrates a Bayesian workflow of model fitting and checking using R and Stan. It was inspired by me reading ‘Visualizing the Bayesian Workflow’ and writing lecture notes1 incorporating ideas in this paper.2 The paper presents a systematic workflow of visualizing the assumptions made in the modeling process, the model fit and comparison of different candidate models.

The goal of this post is to illustrate these steps in an accessible way, applied to a dataset on birth weight and gestational age. It’s a bit of a choose your own adventure in some parts, because as is usually the case in R, there’s about 100 different ways of doing the same thing. I show how to run things using both Stan and with the package brms, which is a wrapper for Stan that allows you to specify models in a similar way to glm or lme4. Using Stan for this example is a bit of overkill because the models are simple, but I find it useful to see what’s going on (and also it’s useful to build up more complex models in Stan from simple ones).

The data

I’m using (a sample of) the publicly available dataset of all births in the United States in 2017, available on the NBER website. For the purposes of this exercise, I’m just using a 0.1% sample of the births, which leads to 3842 observations. Details on how I got the data are here.

Let’s load in the packages we need and the dataset:

library(tidyverse)

library(rstan)

library(brms)

library(bayesplot)

library(loo)

library(tidybayes)

ds <- read_rds("births_2017_sample.RDS")

head(ds)## # A tibble: 6 x 8

## mager mracehisp meduc bmi sex combgest dbwt ilive

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 16 2 2 23 M 39 3.18 Y

## 2 25 7 2 43.6 M 40 4.14 Y

## 3 27 2 3 19.5 F 41 3.18 Y

## 4 26 1 3 21.5 F 36 3.40 Y

## 5 28 7 2 40.6 F 34 2.71 Y

## 6 31 7 3 29.3 M 35 3.52 YThe dataset contains a few different variables, but for the purposes of this exercise I’m going to focus on birth weight and gestational age. Let’s rename these variables, make a preterm variable (which indicates whether or not gestational length was less than 32 weeks)3 and filter out unknown observations, and any babies that died.

ds <- ds %>%

rename(birthweight = dbwt, gest = combgest) %>%

mutate(preterm = ifelse(gest<32, "Y", "N")) %>%

filter(ilive=="Y",gest< 99, birthweight<9.999)Super brief EDA

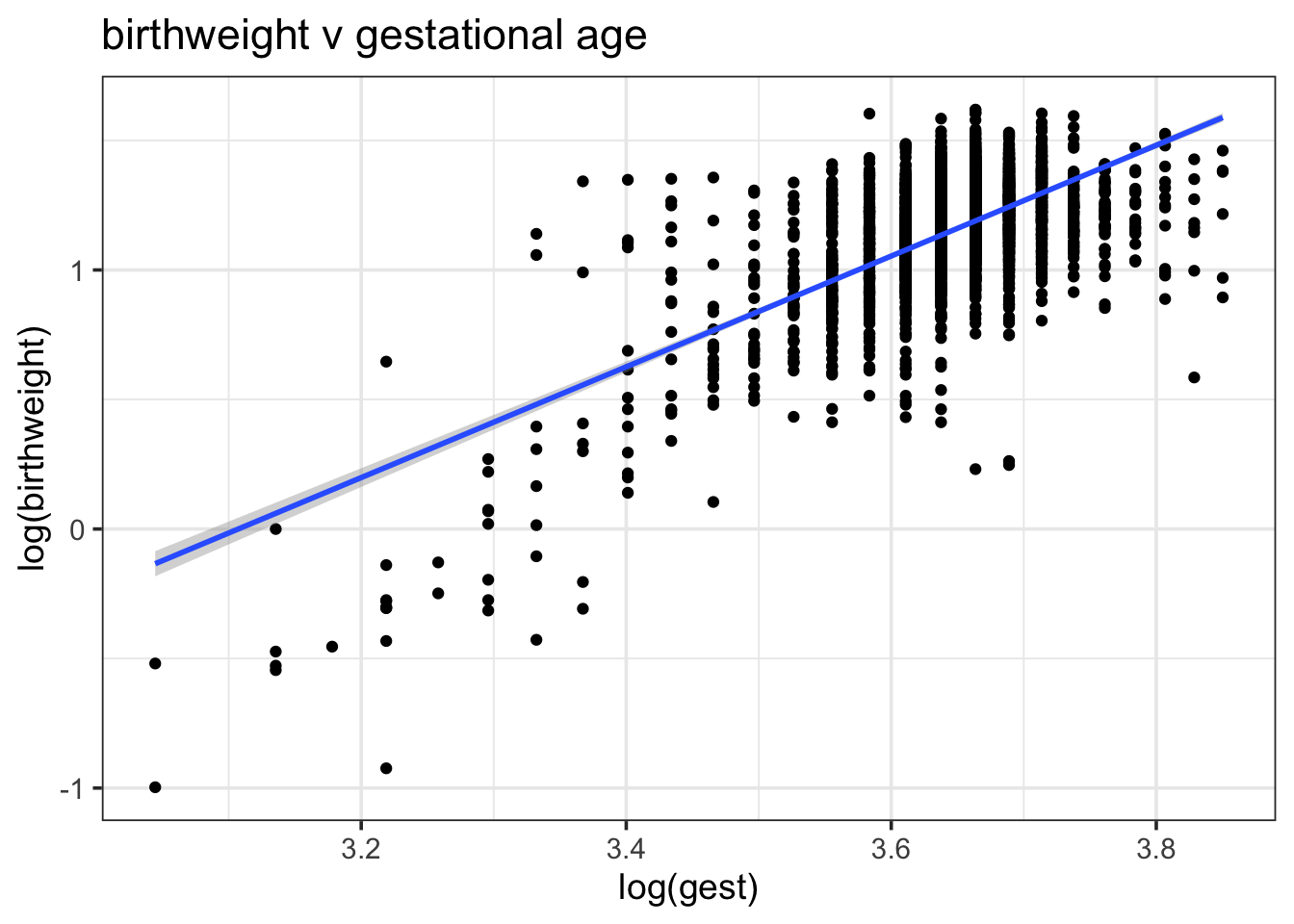

An important first step to model building is exploratory data analysis, which should help to inform potential variables or functional forms of the model. Here’s some EDA in the most brief sense.4 Below is a scatter plot of gestational age (weeks) and birth weight (kg) on the log scale, which appears to show some relationship:

ds %>%

ggplot(aes(log(gest), log(birthweight))) +

geom_point() + geom_smooth(method = "lm") +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

theme_bw(base_size = 14) +

ggtitle("birthweight v gestational age")

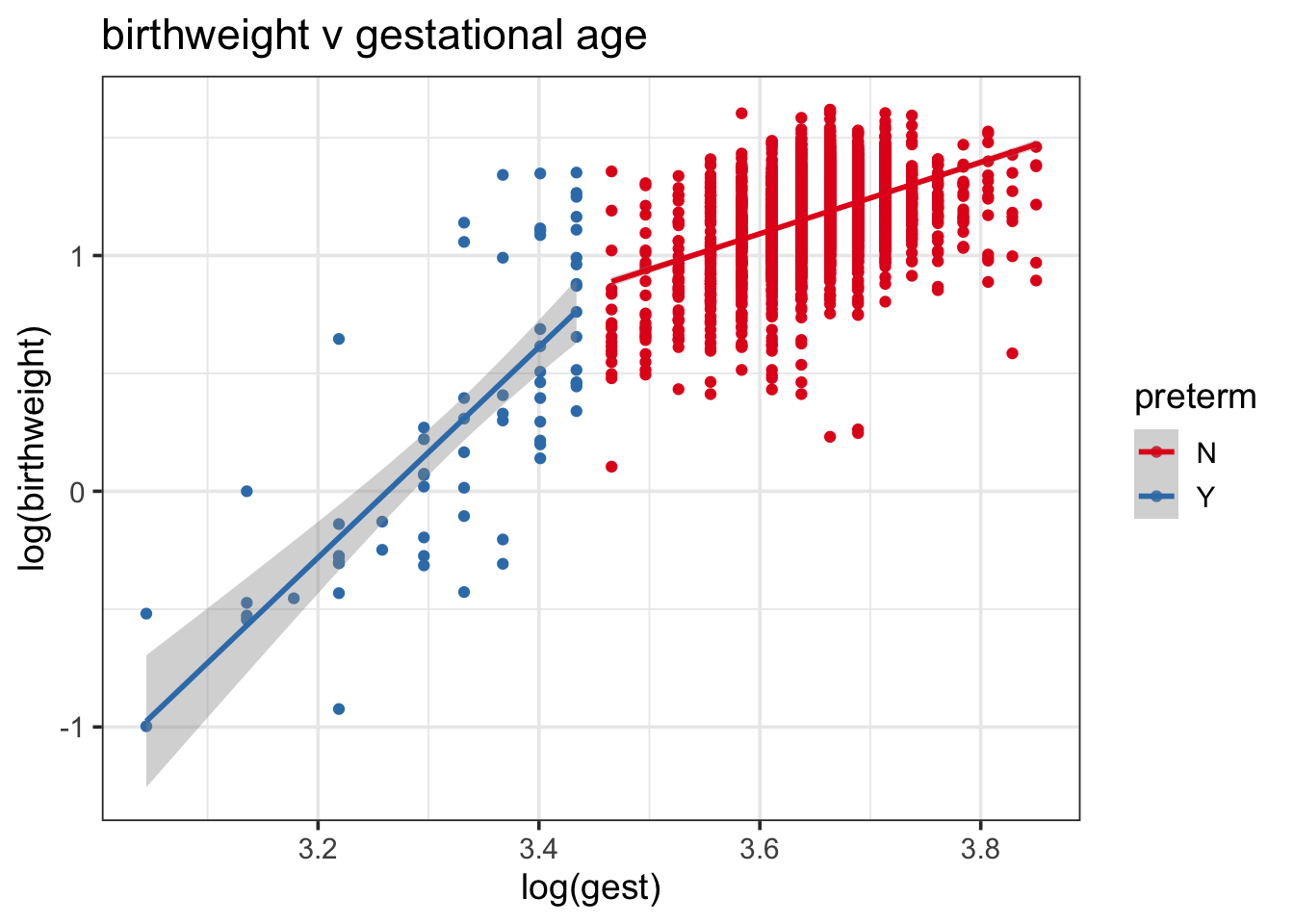

It may be reasonable to allow for the relationship between weight and gestational age to vary by whether or not the baby was premature. If we split by prematurity, there is some evidence to suggest a different relationship between the two variables, which may lead us to consider interaction terms:

ds %>%

ggplot(aes(log(gest), log(birthweight), color = preterm)) +

geom_point() + geom_smooth(method = "lm") +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

theme_bw(base_size = 14) +

ggtitle("birthweight v gestational age")

Some simple candidate models

Based on my super-brief-EDA(tm) I’ve come up with two candidate models. Model 1 has log birth weight as a function of log gestational age

Model 2 has an interaction term between gestation and prematurity

- is weight in kg

- is gestational age in weeks

- is preterm (0 or 1, if gestational age is less than 32 weeks)

Prior predictive checks

Now we have some candidate models in terms of the likelihood, we need to set some priors for our coefficients (s and s) and for the term.

With prior predictive checks, we are essentially looking at the situation where we do not have any data on birthweights at all, and seeing what distribution of weights are implied by the choice of priors and likelihood. Ideally this distribution would have at least some mass around all plausible data sets.

To do this in R, we simulate from the priors and likelihood, and plot the resulting distribution.

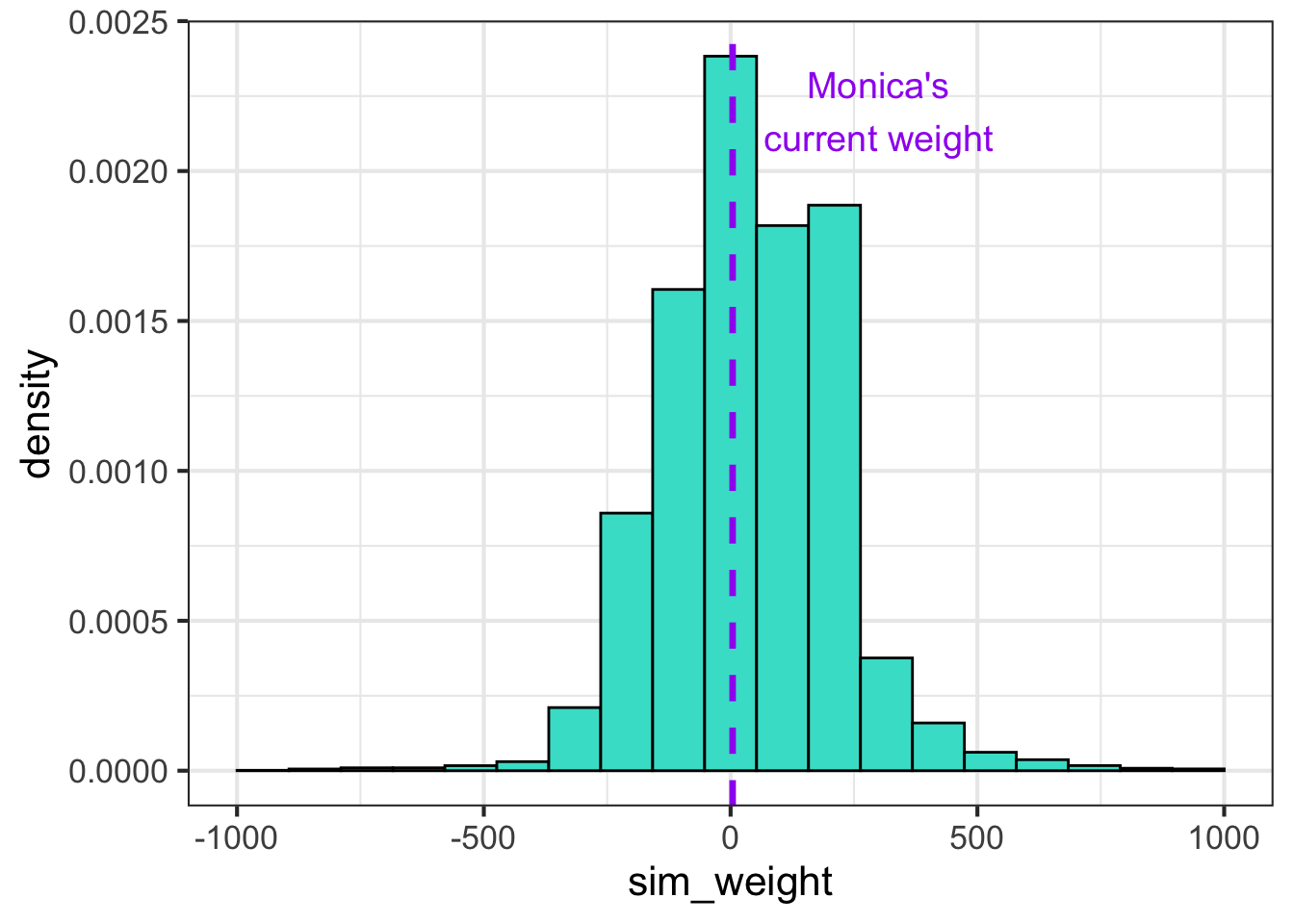

Vague priors

For example, the following plots the prior predictive distribution with vague priors on sigma, and the betas for Model 1. For reference, my current weight is marked with the purple line. While I can attest to babies feeling like they have the mass of a small planet once you’ve been carrying them for 9 months, it’s highly implausible that my current adult weight should have so much probability mass assigned to it.

set.seed(182)

nsims <- 100

sigma <- 1 / sqrt(rgamma(nsims, 1, rate = 100))

beta0 <- rnorm(nsims, 0, 100)

beta1 <- rnorm(nsims, 0, 100)

dsims <- tibble(log_gest_c = (log(ds$gest)-mean(log(ds$gest)))/sd(log(ds$gest)))

for(i in 1:nsims){

this_mu <- beta0[i] + beta1[i]*dsims$log_gest_c

dsims[paste0(i)] <- this_mu + rnorm(nrow(dsims), 0, sigma[i])

}

dsl <- dsims %>%

pivot_longer(`1`:`10`, names_to = "sim", values_to = "sim_weight")

dsl %>%

ggplot(aes(sim_weight)) + geom_histogram(aes(y = ..density..), bins = 20, fill = "turquoise", color = "black") +

xlim(c(-1000, 1000)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = log(60), color = "purple", lwd = 1.2, lty = 2) +

theme_bw(base_size = 16) +

annotate("text", x=300, y=0.0022, label= "Monica's\ncurrent weight",

color = "purple", size = 5)

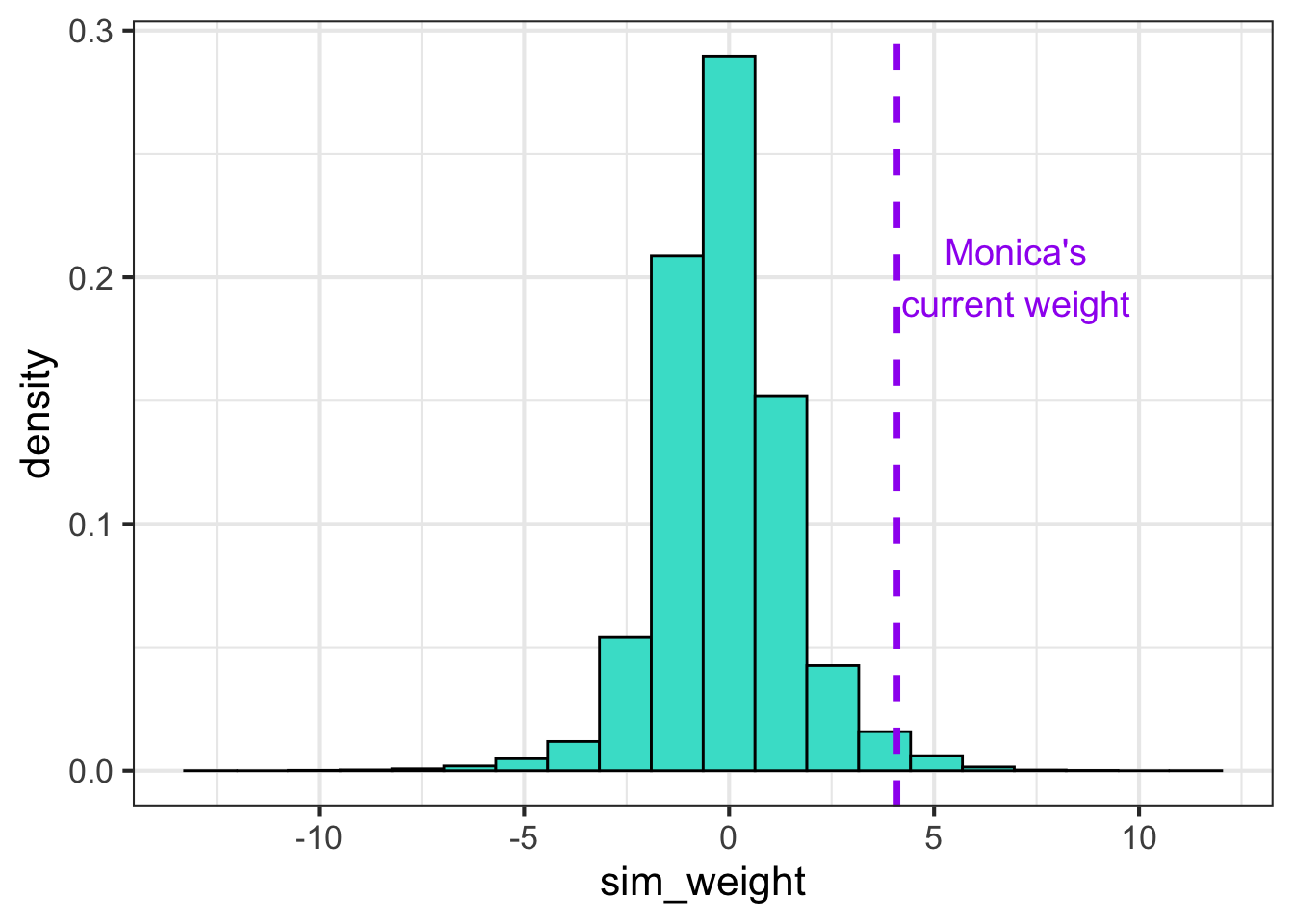

Weakly informative priors

Let’s try this exercise again, but now with some weakly informative priors. The distribution is much less spread out, and my current weight is now much further to the right of the distribution. Remember that these are the distributions before we look at any data, and we are doing so just to make sure that any plausible values have some probability of showing up. The picture will look much different once we take the observations into account.

sigma <- abs(rnorm(nsims, 0, 1))

beta0 <- rnorm(nsims, 0, 1)

beta1 <- rnorm(nsims, 0, 1)

dsims <- tibble(log_gest_c = (log(ds$gest)-mean(log(ds$gest)))/sd(log(ds$gest)))

for(i in 1:nsims){

this_mu <- beta0[i] + beta1[i]*dsims$log_gest_c

dsims[paste0(i)] <- this_mu + rnorm(nrow(dsims), 0, sigma[i])

}

dsl <- dsims %>%

pivot_longer(`1`:`10`, names_to = "sim", values_to = "sim_weight")

dsl %>%

ggplot(aes(sim_weight)) + geom_histogram(aes(y = ..density..), bins = 20, fill = "turquoise", color = "black") +

geom_vline(xintercept = log(60), color = "purple", lwd = 1.2, lty = 2) +

theme_bw(base_size = 16) +

annotate("text", x=7, y=0.2, label= "Monica's\ncurrent weight", color = "purple", size = 5)

Run the models

Now let’s run the models described above. I will illustrate how to do this in both stan and brms.

Running the models in Stan

The Stan code for model 1 is below. You can view the stan code for model 2 here. It’s worth noticing the generated quantities block: for our model checks later on, we need to generate 1) pointwise estimates of the log-likelihood and 2) samples from the posterior predictive distribution. When using brms we don’t have to worry about this because the log-likelihood is calculated by default, and the posterior predictive samples can be generated afterwards.5

data {

int<lower=1> N; // number of observations

vector[N] log_gest; // log gestational age

vector[N] log_weight; // log birth weight

}

parameters {

vector[2] beta; // coefs

real<lower=0> sigma; // error sd for Gaussian likelihood

}

model {

// Log-likelihood

target += normal_lpdf(log_weight | beta[1] + beta[2] * log_gest, sigma);

// Log-priors

target += normal_lpdf(sigma | 0, 1)

+ normal_lpdf(beta | 0, 1);

}

generated quantities {

vector[N] log_lik; // pointwise log-likelihood for LOO

vector[N] log_weight_rep; // replications from posterior predictive dist

for (n in 1:N) {

real log_weight_hat_n = beta[1] + beta[2] * log_gest[n];

log_lik[n] = normal_lpdf(log_weight[n] | log_weight_hat_n, sigma);

log_weight_rep[n] = normal_rng(log_weight_hat_n, sigma);

}

}Calculate the transformed variables, and put the data into a list for Stan.

ds$log_weight <- log(ds$birthweight)

ds$log_gest_c <- (log(ds$gest) - mean(log(ds$gest)))/sd(log(ds$gest))

N <- nrow(ds)

log_weight <- ds$log_weight

log_gest_c <- ds$log_gest_c

preterm <- ifelse(ds$preterm=="Y", 1, 0)

# put into a list

stan_data <- list(N = N,

log_weight = log_weight,

log_gest = log_gest_c,

preterm = preterm)Running the models in Stan looks like this:

mod1 <- stan(data = stan_data,

file = "models/simple_weight.stan",

iter = 500,

seed = 243)

mod2 <- stan(data = stan_data,

file = "models/simple_weight_preterm_int.stan",

iter = 500,

seed = 263)Take a look at the estimates of parameters of interest. Note that I centered and standardized the gestation variable, so the interpretation in Model 1 for example is that a 1 standard deviation increase in the gestation weeks leads to a 0.14% increase in birth weight.

summary(mod1)[["summary"]][c(paste0("beta[",1:2, "]"), "sigma"),]## mean se_mean sd 2.5% 25% 50%

## beta[1] 1.1624438 1.064120e-04 0.002811842 1.1570794 1.1606196 1.1623062

## beta[2] 0.1439831 9.066275e-05 0.002617224 0.1388411 0.1421880 0.1439459

## sigma 0.1690629 1.952945e-04 0.001996376 0.1646983 0.1679532 0.1690067

## 75% 97.5% n_eff Rhat

## beta[1] 1.1642252 1.1687179 698.2338 0.9997474

## beta[2] 0.1457571 0.1492866 833.3437 1.0007247

## sigma 0.1703736 0.1730148 104.4972 1.0432960For Model 2, the third relates to the effect of prematury, and the fourth is the interaction. The interaction effect suggests that the increase in birthweight with increased gestational age is more steep from premature babies.

summary(mod2)[["summary"]][c(paste0("beta[",1:4, "]"), "sigma"),]## mean se_mean sd 2.5% 25% 50%

## beta[1] 1.1695780 1.098568e-04 0.002644516 1.16468175 1.16781334 1.1697444

## beta[2] 0.1016943 1.466149e-04 0.003430911 0.09486125 0.09943203 0.1016294

## beta[3] 0.5602261 8.680419e-03 0.068807739 0.42911843 0.51286040 0.5558835

## beta[4] 0.1983536 1.635249e-03 0.014126383 0.17212096 0.18833129 0.1975351

## sigma 0.1613039 9.611339e-05 0.001818344 0.15803181 0.15991605 0.1612618

## 75% 97.5% n_eff Rhat

## beta[1] 1.1712703 1.1745931 579.47951 1.0026436

## beta[2] 0.1037481 0.1085696 547.59919 0.9940805

## beta[3] 0.6111351 0.6989987 62.83378 1.0631488

## beta[4] 0.2081473 0.2260562 74.62672 1.0439166

## sigma 0.1626634 0.1651492 357.91841 1.0083042Running the models in brms

Running the models in brms looks like this:

mod1b <- brm(log_weight~log_gest_c, data = ds)

mod2b <- brm(log_weight~log_gest_c*preterm, data = ds)Posterior predictive checks

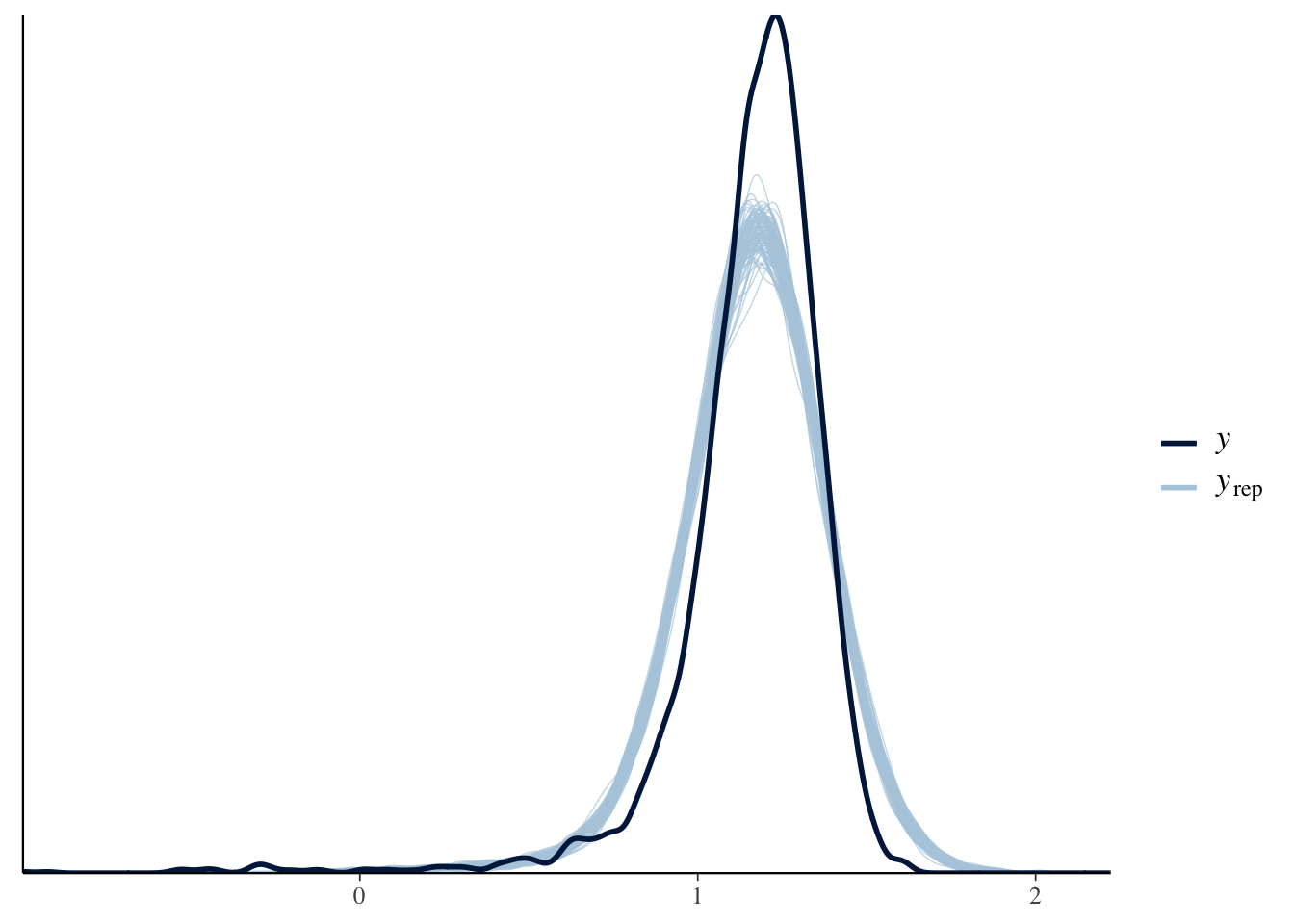

Now we’ve run the models, let’s do some posterior predictive checks. The idea of posterior predictive checks is to compare our observed data to replicated data from the model. If our model is a good fit, we should be able to use it to generate a dataset that resembles the observed data.

PPCs with Stan output

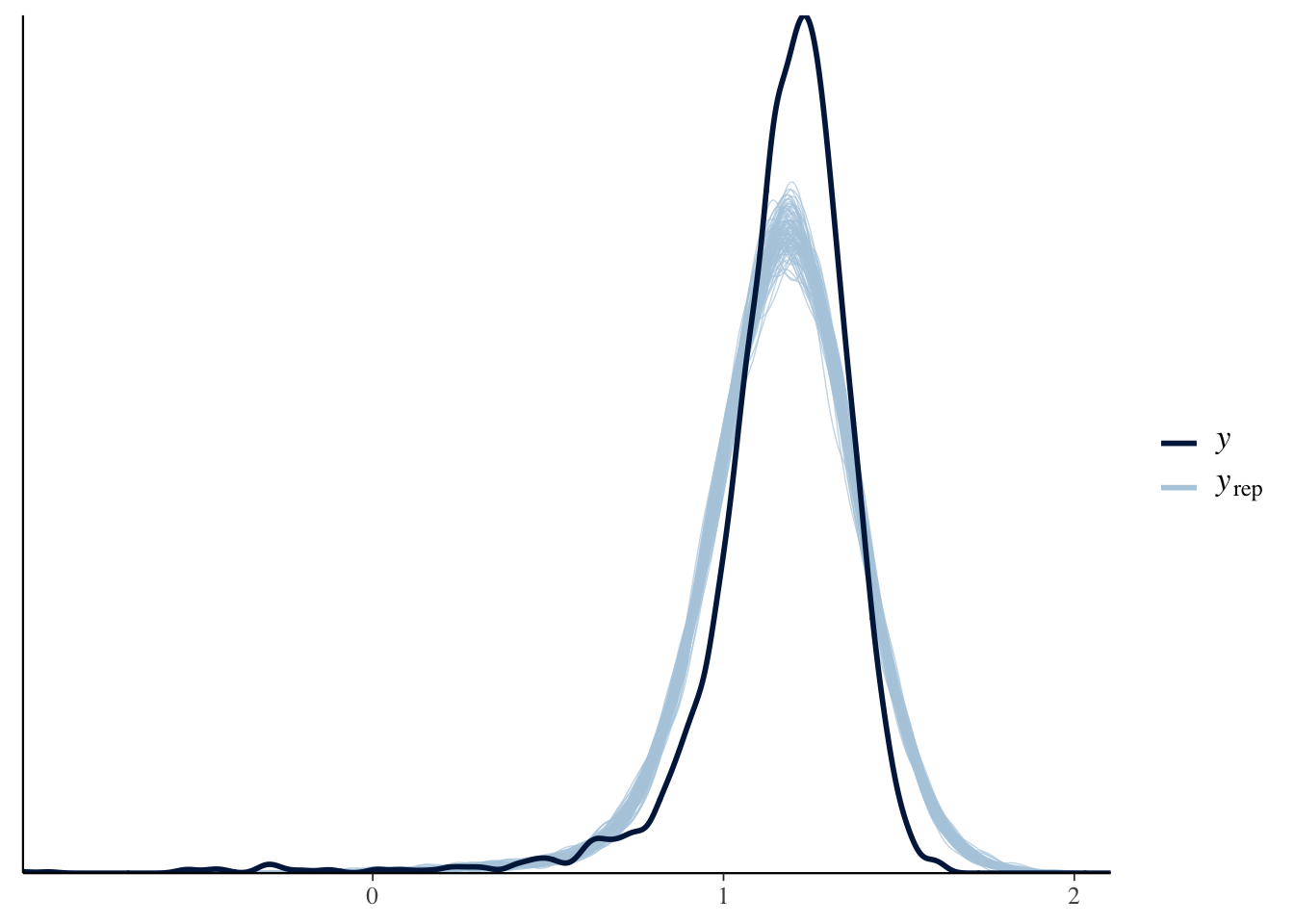

For the Stan models, we want to extract the samples from the posterior predictive distribution and can then use ppc_dens_overlay to compare the densities of 100 sampled datasets to the actual data:

set.seed(1856)

y <- log_weight

yrep1 <- extract(mod1)[["log_weight_rep"]]

samp100 <- sample(nrow(yrep1), 100)

ppc_dens_overlay(y, yrep1[samp100, ])

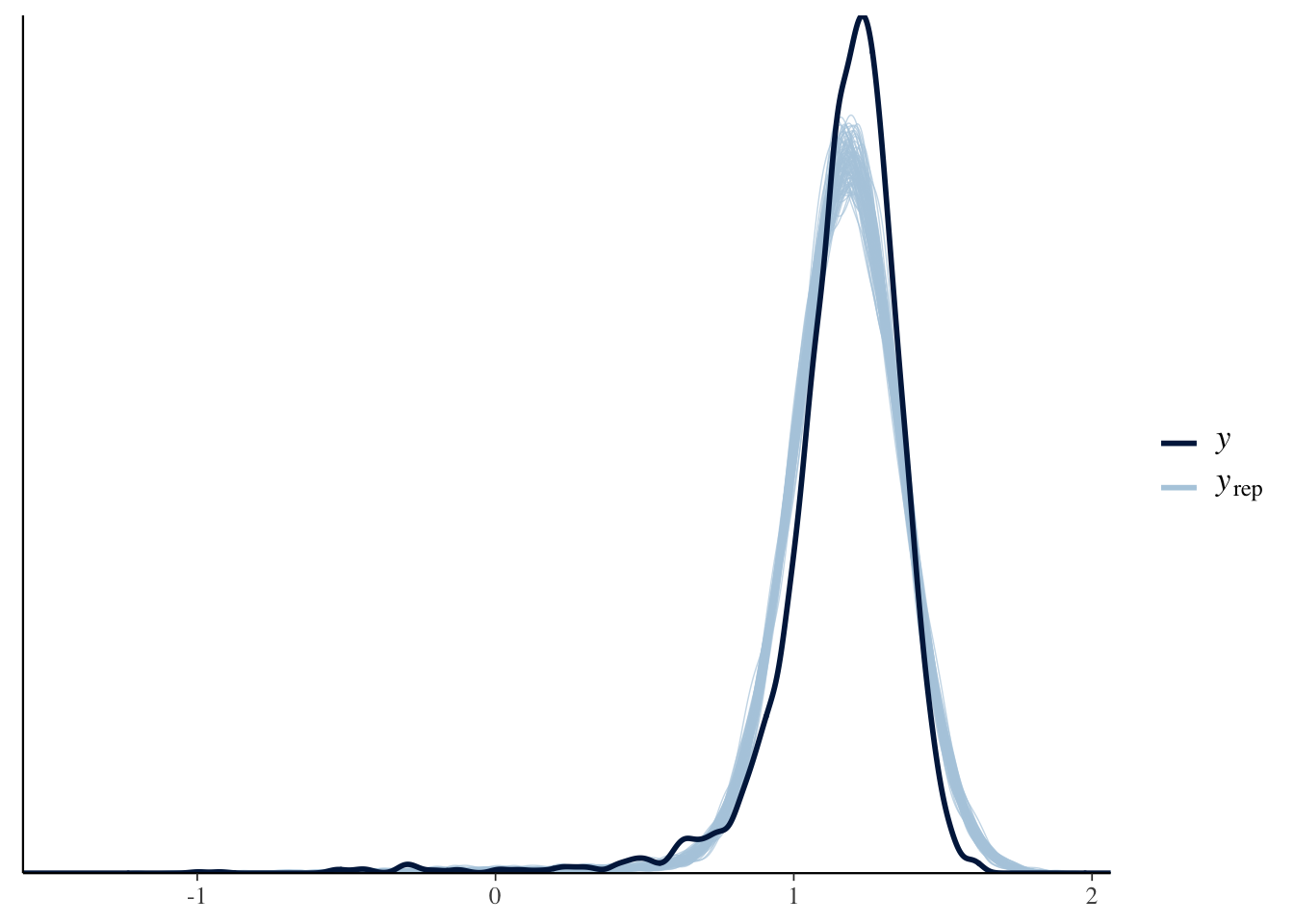

Model 2 is a bit better:

yrep2 <- extract(mod2)[["log_weight_rep"]]

ppc_dens_overlay(y, yrep2[samp100, ])

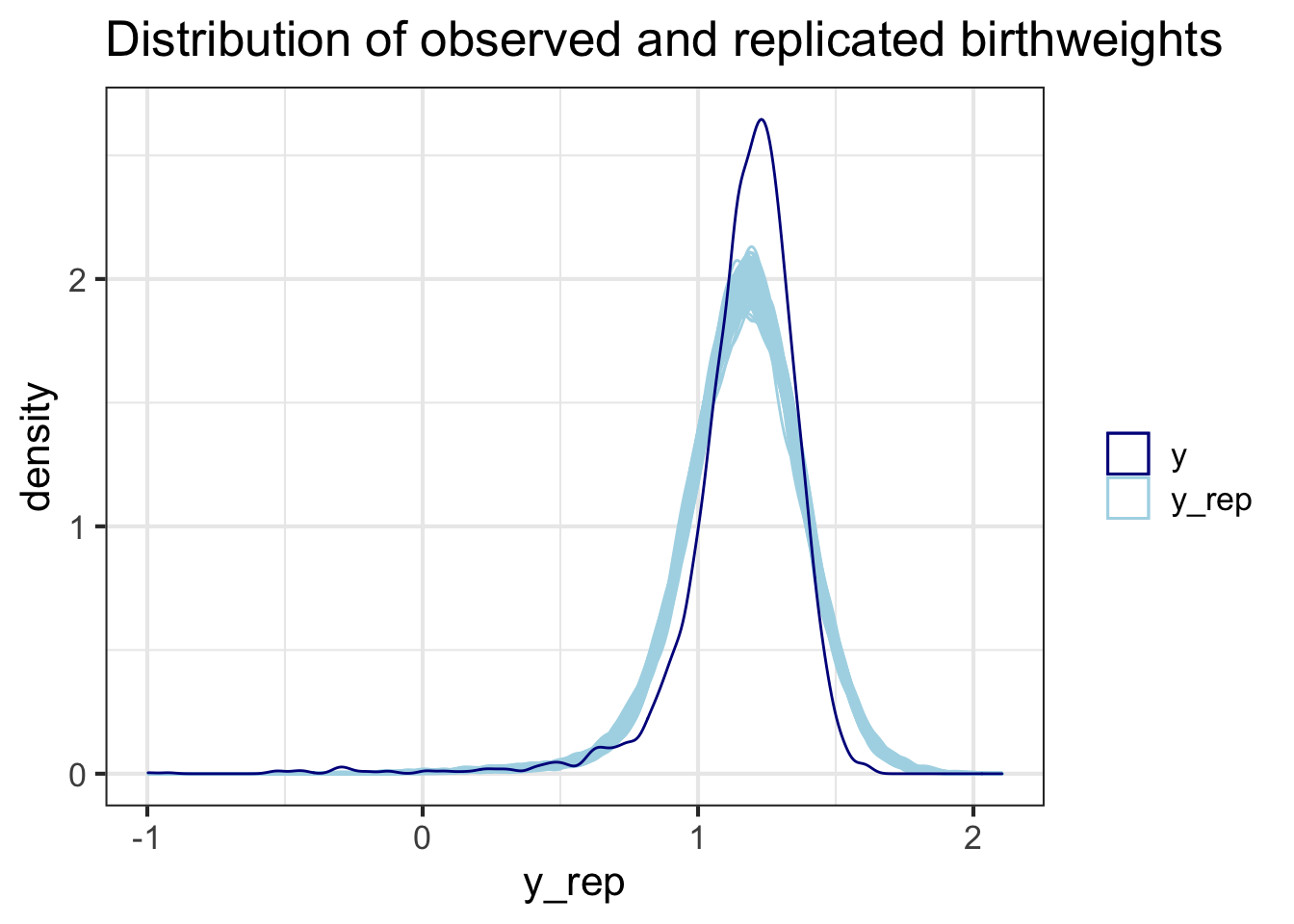

If you would like to convince yourself you know what’s going on with ppc_dens_overlay or would like to format your graphs from scratch, you can do the density plots yourself:

# first, get into a tibble

rownames(yrep1) <- 1:nrow(yrep1)

dr <- as_tibble(t(yrep1))

dr <- dr %>% bind_cols(i = 1:N, log_weight_obs = log(ds$birthweight))

# turn into long format; easier to plot

dr <- dr %>%

pivot_longer(-(i:log_weight_obs), names_to = "sim", values_to ="y_rep")

# filter to just include 100 draws and plot!

dr %>%

filter(sim %in% samp100) %>%

ggplot(aes(y_rep, group = sim)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2, aes(color = "y_rep")) +

geom_density(data = ds %>% mutate(sim = 1),

aes(x = log(birthweight), col = "y")) +

scale_color_manual(name = "",

values = c("y" = "darkblue",

"y_rep" = "lightblue")) +

ggtitle("Distribution of observed and replicated birthweights") +

theme_bw(base_size = 16)

Test statistics

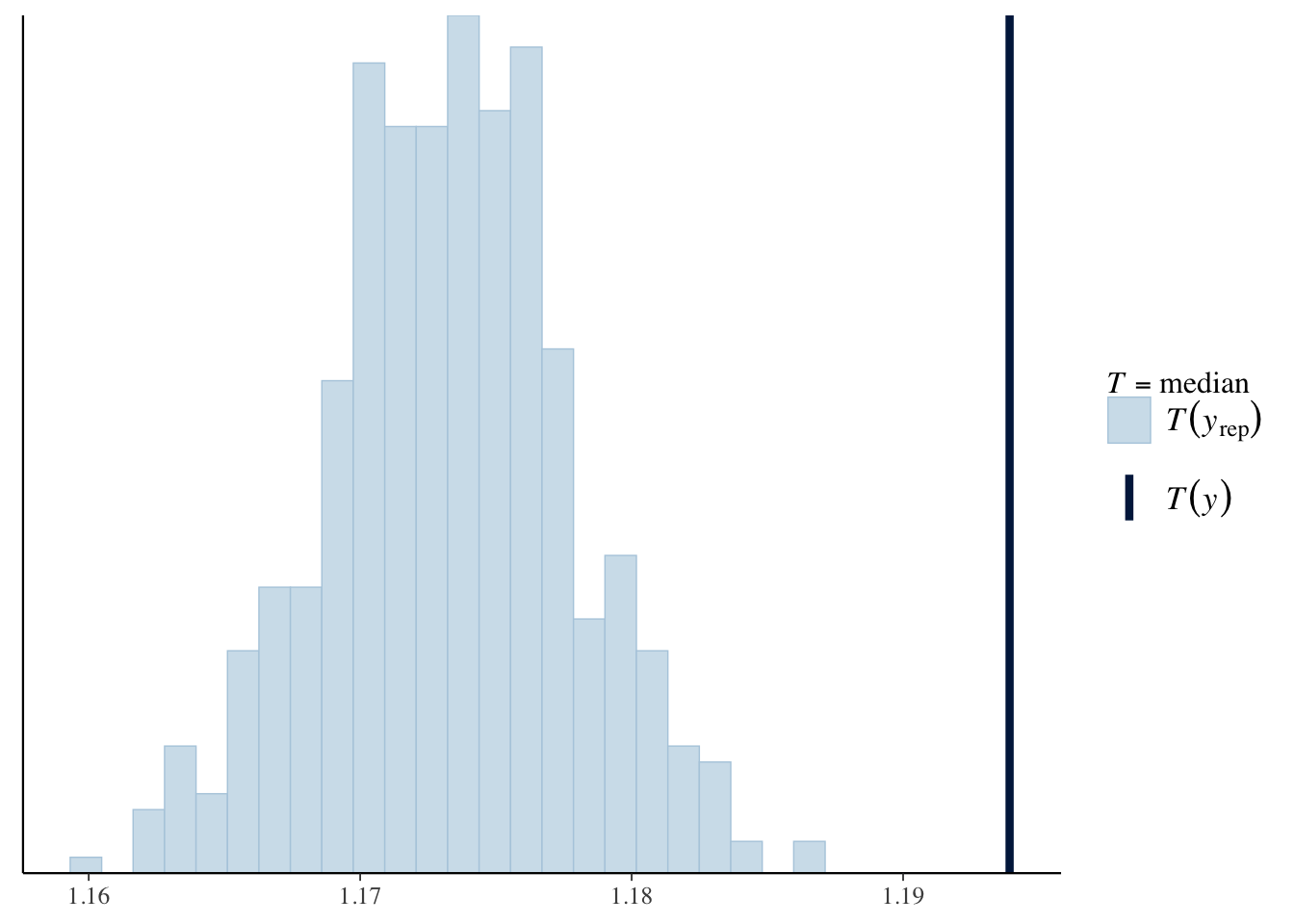

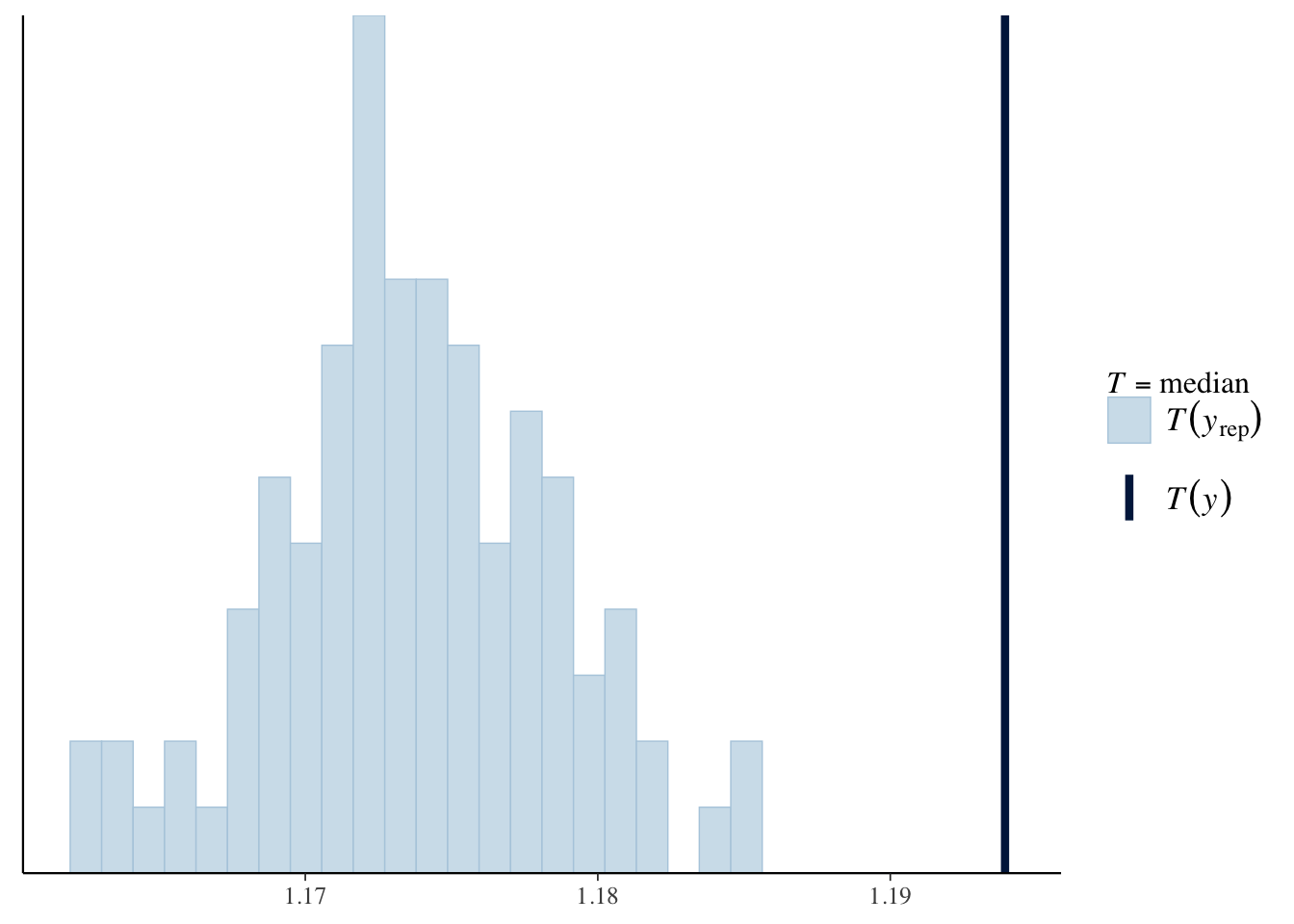

As well as looking at the overall distributions of the replicated datasets versus the data, we can decide on a test statistic(s) that is a summary of interest, calculate the statistic for each replicated dataset, and compare the distribution of these values with the value of the statistic observed in the data.

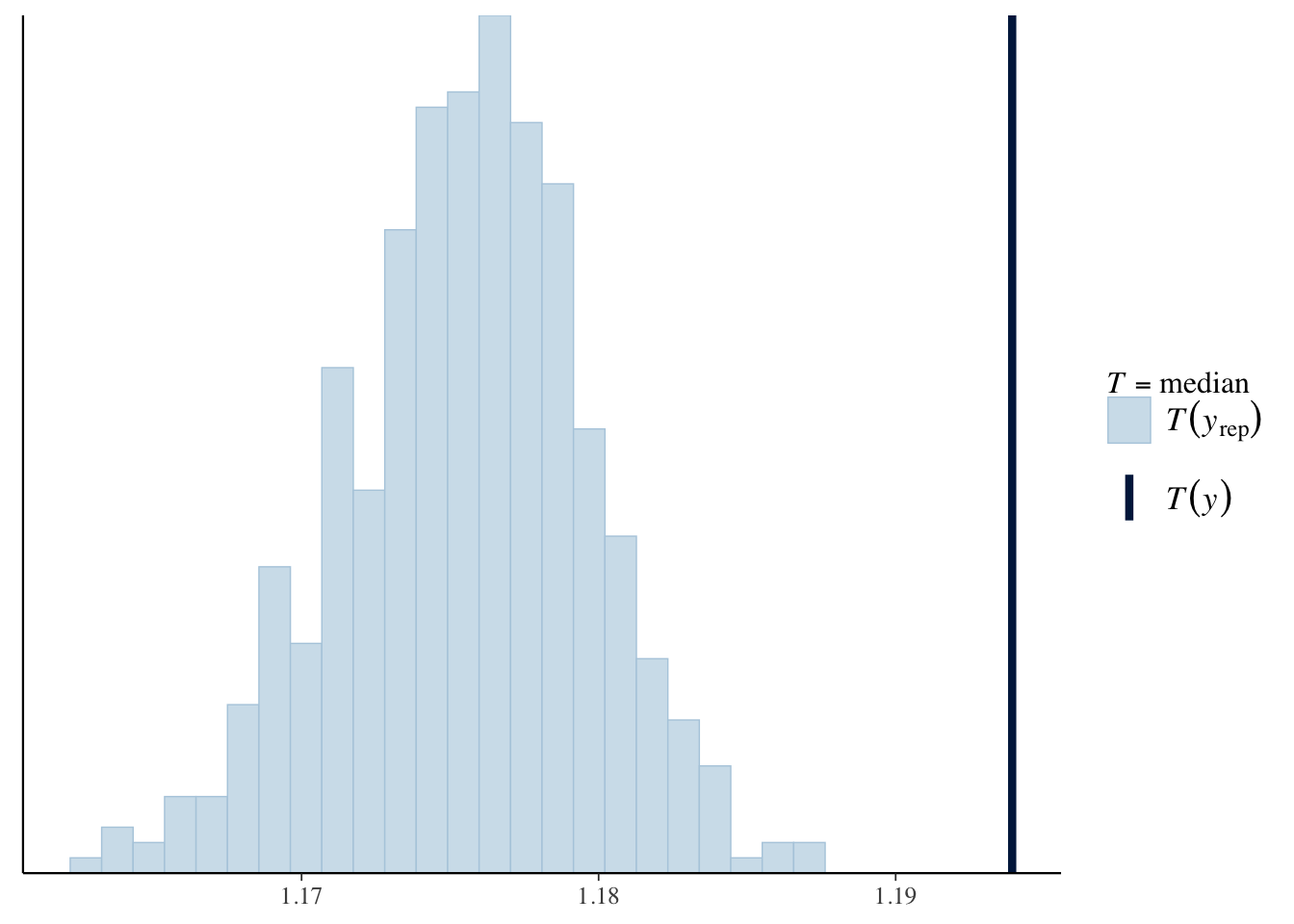

For example, we can look at the distribution of the median (log) birth weight across the replicated data sets in comparison to the median in the data, and plot using ppc_stat. For both models, the predicted median birth weight is too low.

ppc_stat(log_weight, yrep1, stat = 'median')

ppc_stat(log_weight, yrep2, stat = 'median')

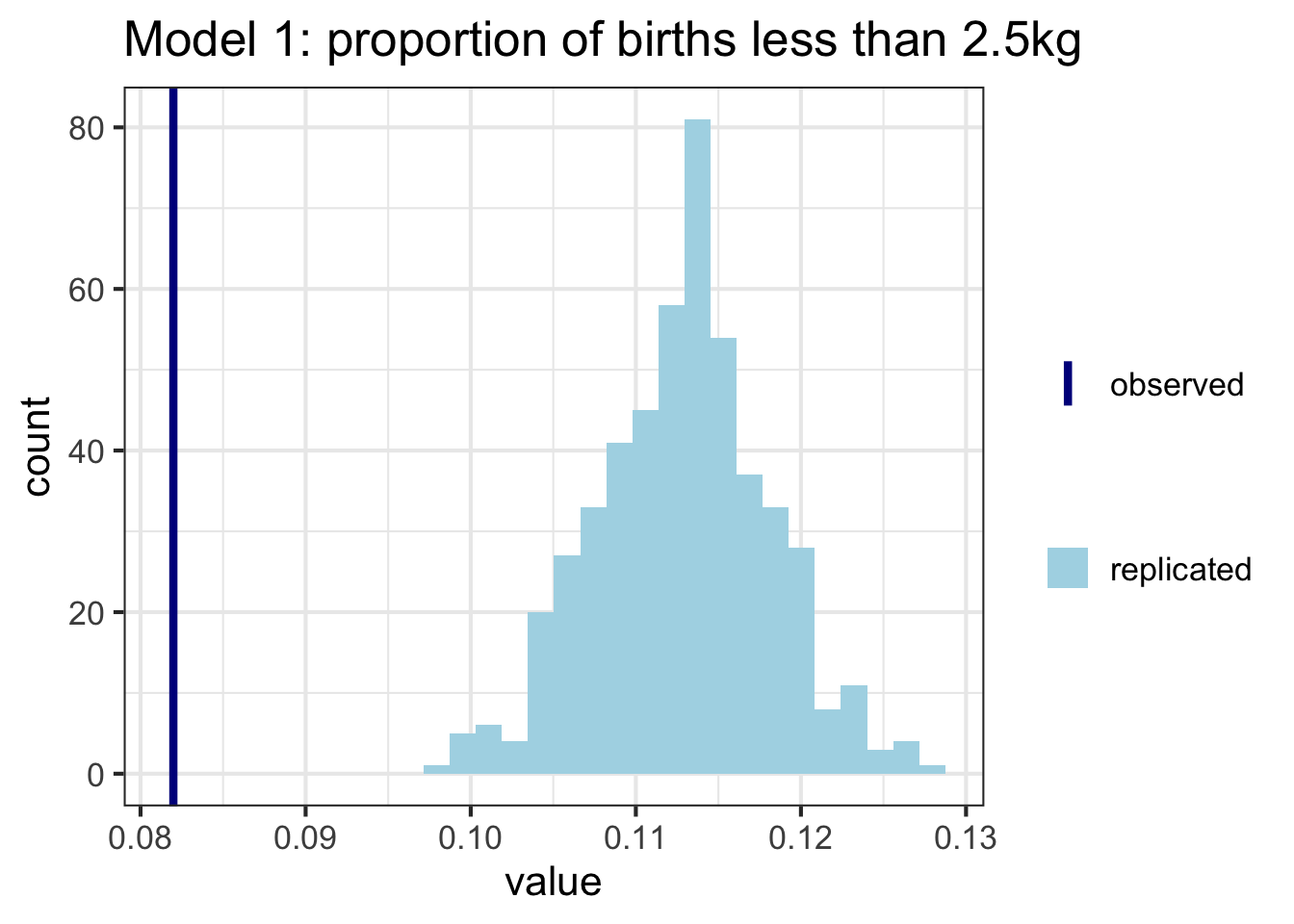

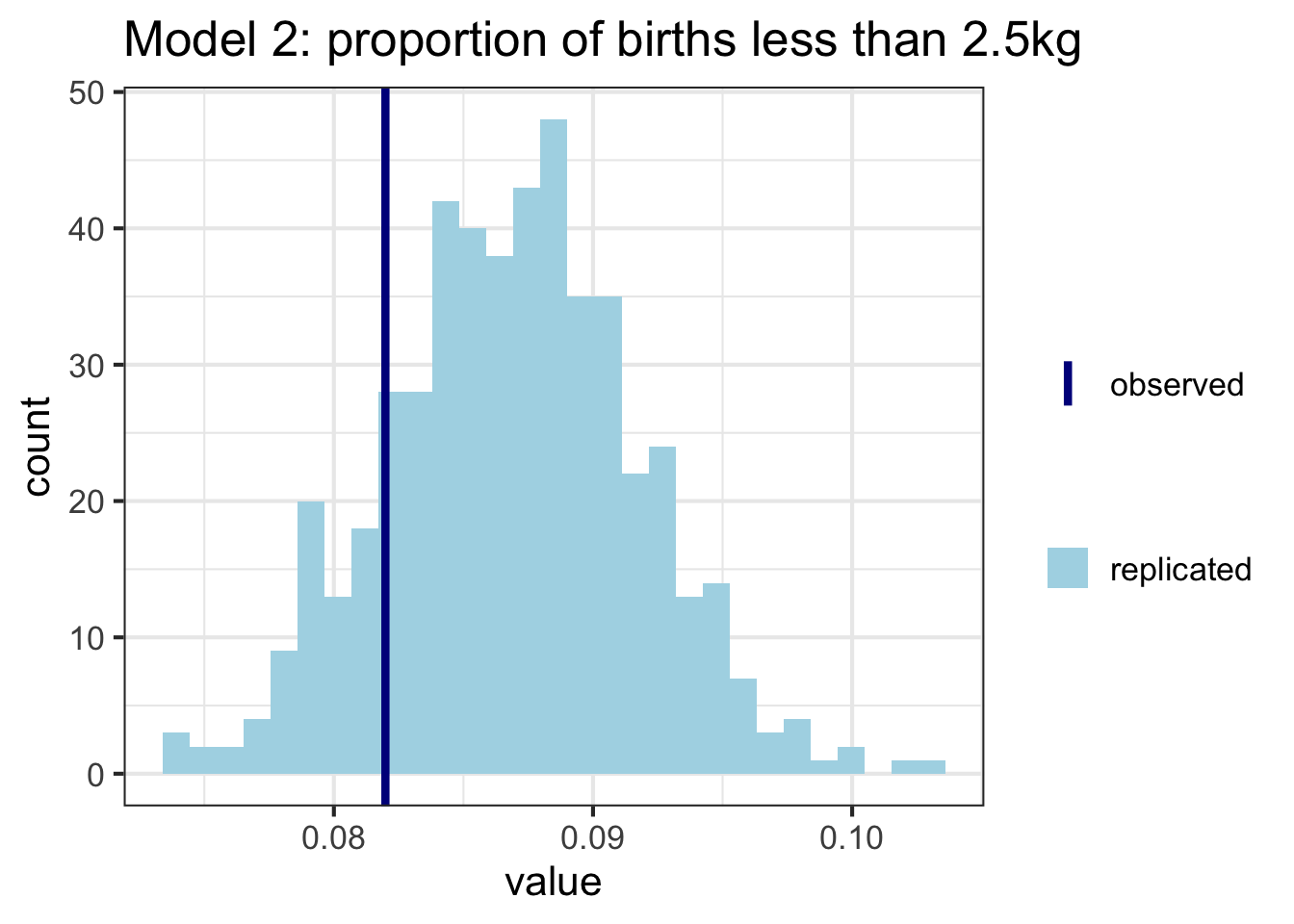

As before, we can also construct these plots ourselves. Here I’m calculating the proportion of babies who have a weight less than 2.5kg (considered low birth weight) in each of the replicated datasets, and comparing to the proportion in the data. Model 2 seems to do a better job here:

t_y <- mean(y<=log(2.5))

t_y_rep <- sapply(1:nrow(yrep1), function(i) mean(yrep1[i,]<=log(2.5)))

t_y_rep_2 <- sapply(1:nrow(yrep2), function(i) mean(yrep2[i,]<=log(2.5)))

ggplot(data = as_tibble(t_y_rep), aes(value)) +

geom_histogram(aes(fill = "replicated")) +

geom_vline(aes(xintercept = t_y, color = "observed"), lwd = 1.5) +

ggtitle("Model 1: proportion of births less than 2.5kg") +

theme_bw(base_size = 16) +

scale_color_manual(name = "",

values = c("observed" = "darkblue"))+

scale_fill_manual(name = "",

values = c("replicated" = "lightblue"))

ggplot(data = as_tibble(t_y_rep_2), aes(value)) +

geom_histogram(aes(fill = "replicated")) +

geom_vline(aes(xintercept = t_y, color = "observed"), lwd = 1.5) +

ggtitle("Model 2: proportion of births less than 2.5kg") +

theme_bw(base_size = 16) +

scale_color_manual(name = "",

values = c("observed" = "darkblue"))+

scale_fill_manual(name = "",

values = c("replicated" = "lightblue"))

PPCs with brms output

With the models built in brms, we can use the posterior_predict function to get samples from the posterior predictive distribution:

yrep1b <- posterior_predict(mod1b)Alterantively, you can use the tidybayes package to add predicted draws to the original ds data tibble. This option is nice if you want to do a lot of ggplotting later on, because the data is already in tidy format.

ds_yrep1 <- ds %>%

select(log_weight, log_gest_c) %>%

add_predicted_draws(mod1b)

head(ds_yrep1)## # A tibble: 6 x 7

## # Groups: log_weight, log_gest_c, .row [1]

## log_weight log_gest_c .row .chain .iteration .draw .prediction

## <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl>

## 1 1.16 0.188 1 NA NA 1 1.21

## 2 1.16 0.188 1 NA NA 2 1.16

## 3 1.16 0.188 1 NA NA 3 1.14

## 4 1.16 0.188 1 NA NA 4 1.38

## 5 1.16 0.188 1 NA NA 5 0.975

## 6 1.16 0.188 1 NA NA 6 0.893Once you have the posterior predictive samples, you can use the bayesplot package as we did above with the Stan output, or do the plots yourself in ggplot.

Another quick alternative with brms that avoids manually getting the posterior predictive samples altogether is to use the pp_check function, which is a wrapper for all the bayesplot options. e.g. density overlays:

pp_check(mod1b, type = "dens_overlay", nsamples = 100)

e.g. test statistics:

pp_check(mod1b, type = "stat", stat = 'median', nsamples = 100)

LOO-CV

The last piece of this workflow is comparing models using leave-one-out cross validation. We are interested in estimating the out-of-sample predictive accuracy at each point , when all we have to fit the model is data that without point . We want to estimate the leave-one-out (LOO) posterior predictive densities and a summary of these across all points, which is called the LOO expected log pointwise predictive density (). The bigger the numbers, the better we are at predicting the left out point .

By comparing the () across models, we can choose the model that has the higher value. By looking at values for the individual points, we can see which observations are particularly hard to predict.

To calculate the () in R, we will use the loo package. This estimates the LOO posterior predictive densities using Pareto Smoothed Importance Sampling (PSIS)6, and requires point estimates of the log likelihood.

LOO-CV with Stan output

For the Stan models, we need to extract the log-likelihood, and then run loo. (The save_psis = TRUE is needed for the LOO-PIT graphs below).

loglik1 <- extract(mod1)[["log_lik"]]

loglik2 <- extract(mod2)[["log_lik"]]

loo1 <- loo(loglik1, save_psis = TRUE)

loo2 <- loo(loglik2, save_psis = TRUE)We can look at the summaries of these and also compare across models. The is higher for Model 2, so it is preferred.

loo1##

## Computed from 500 by 3842 log-likelihood matrix

##

## Estimate SE

## elpd_loo 1377.5 72.3

## p_loo 9.0 1.3

## looic -2755.0 144.6

## ------

## Monte Carlo SE of elpd_loo is 0.1.

##

## All Pareto k estimates are good (k < 0.5).

## See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.loo2##

## Computed from 500 by 3842 log-likelihood matrix

##

## Estimate SE

## elpd_loo 1552.0 69.8

## p_loo 16.2 2.6

## looic -3104.0 139.7

## ------

## Monte Carlo SE of elpd_loo is 0.2.

##

## All Pareto k estimates are good (k < 0.5).

## See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.compare(loo1, loo2)## elpd_diff se

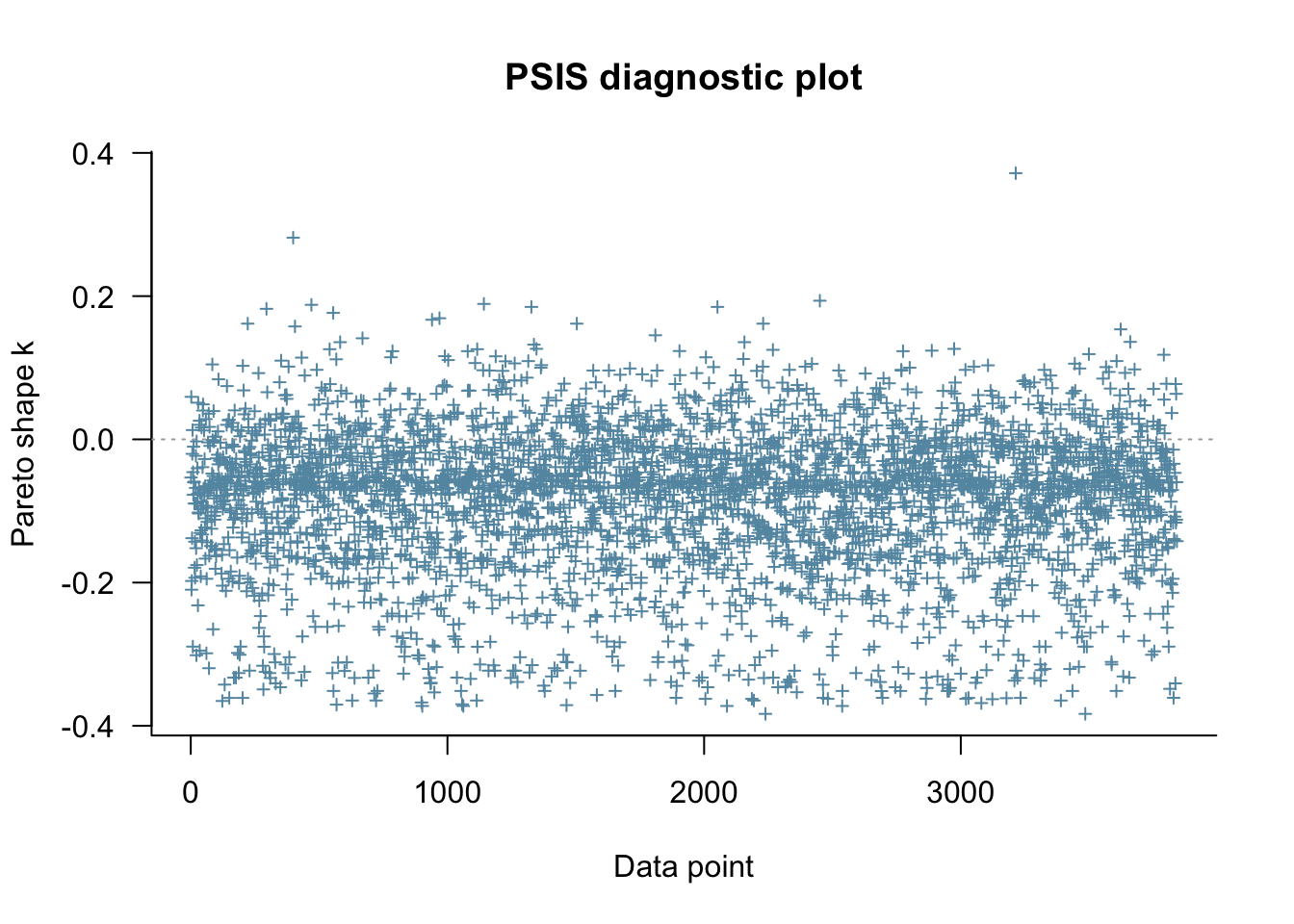

## 174.5 36.3The output mentions Pareto k estimates, which give an indication of how ‘influential’ each point is. The higher the value of , the more influential the point. Values of over 0.7 are not good, and suggest the need for model re-specification. The values of can be extracted from the loo object like this:

head(loo1$diagnostics$pareto_k)## [1] -0.05329232 0.05934065 -0.20993121 -0.19775285 -0.13801892 -0.02027345or plotted easily like this:

plot(loo1)

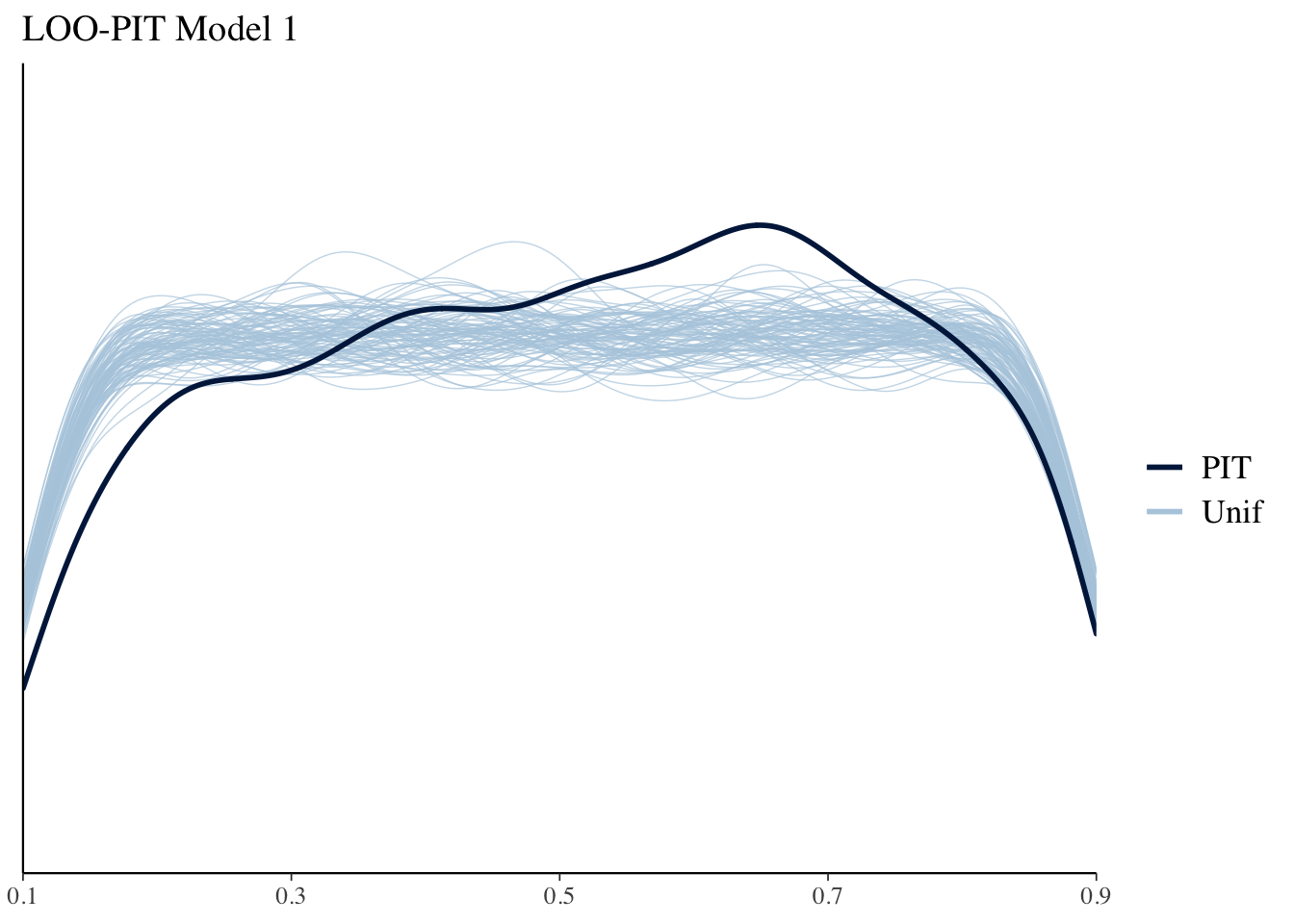

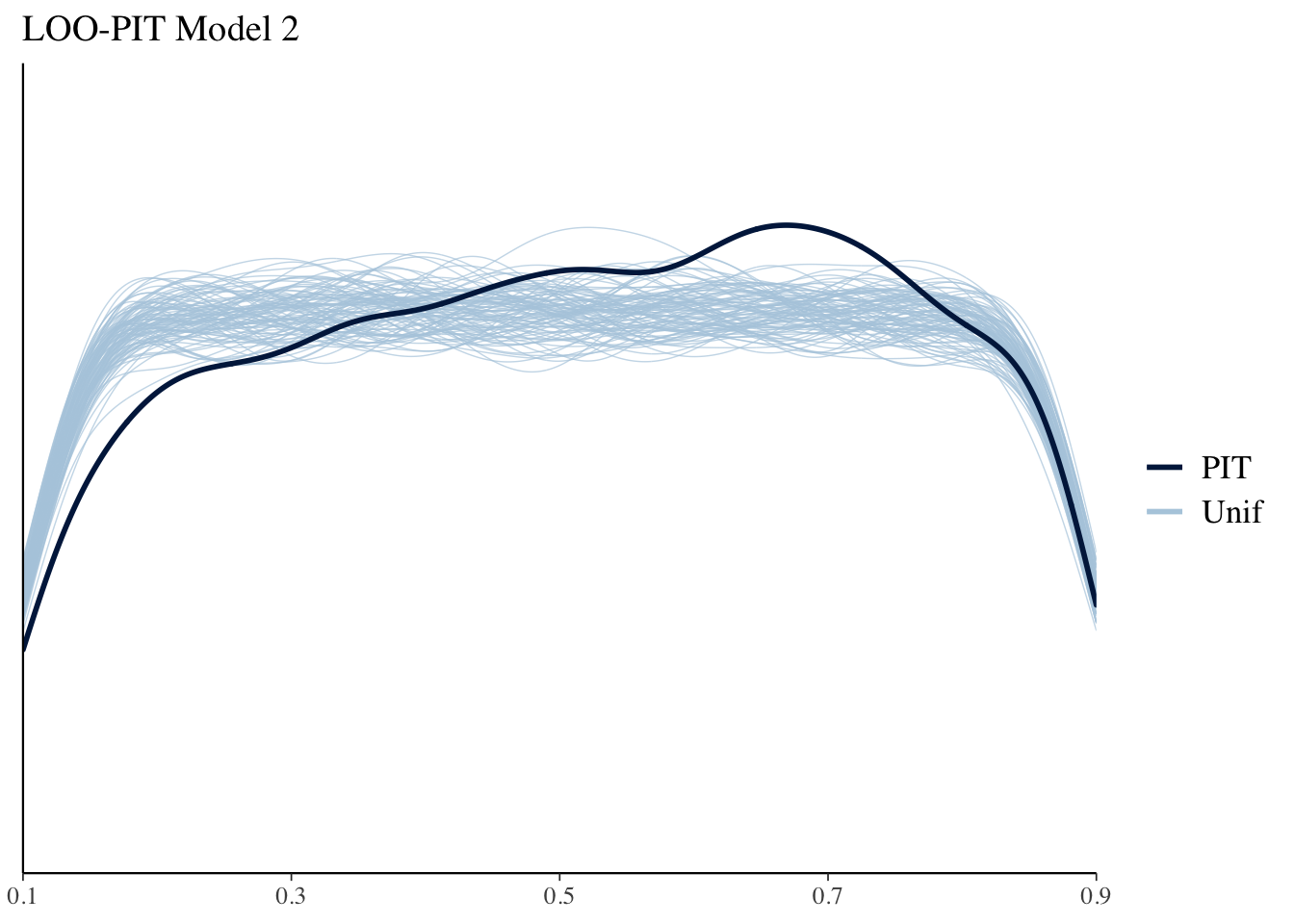

LOO-PIT

Another useful model diagnostic is the LOO probability integral transform (PIT). This essentially looks to see where each point falls in its predictive distribution . If the model is well calibrated these should look like Uniform distributions. We can use bayesplot to plot these against 100 simulate standard Uniforms. The results in this case aren’t too bad.

ppc_loo_pit_overlay(yrep = yrep1, y = y, lw = weights(loo1$psis_object)) + ggtitle("LOO-PIT Model 1")

ppc_loo_pit_overlay(yrep = yrep2, y = y, lw = weights(loo2$psis_object)) + ggtitle("LOO-PIT Model 2")

LOO-CV with brms output

With brms, the log likelihood is calculated automatically, and we can just pass the model objects directly to loo, for example:

loo1b <- loo(mod1b, save_psis = TRUE)Once we have the loo object, the rest of the plots etc can be done as above with the Stan output.

Summary

Visualization is a powerful tool in assessing model assumptions and performance. For Bayesian models, it’s important to think about how priors interplay with the likelihood (even before we observe data), to see how newly predicted data line up with the observed data, and to see how the model performs out of sample. For Bayesian models there are potentially an overwhelming number of different outputs, and in R there are a million different ways to do the same thing, so hopefully this post helps someone wade through these depths, towards a more structured Bayesian workflow.

If any students are reading this, it contains answers for most of the lab questions, lol.↩︎

I am very lucky to work with one of the authors, Dan Simpson, who listens to my questions and comments at length with an admirable level of patience, usually in exchange for coffee.↩︎

Technically this is whether or not the birth was ‘very preterm’ according to WHO definitions: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth↩︎

Someone I know was recently asked “when do you know that your EDA is done?” Their response was, EDA is never done, you just die.↩︎

It’s also possible / easy to get posterior predictive samples in R after running the model, here is some example code. Doing everything in Stan is neater, but it might be clearer to see what’s going on doing it yourself in R.↩︎