Reproducibility in demographic research

On October 10-11, I attended the Open Science Workshop at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. Phil Cohen and I gave keynote presentations. Phil, who was one of the driving forces behind SocArxiv, gave a great talk on the importance of open science and practical ways to make it happen.

My presentation focused more specifically on reproducibility in demographic research, why it’s important, and gave an overview of some tools that may be useful. In the spirit of the talk, all the materials to reproduce the slides are here.

Some key take-aways from the talk:

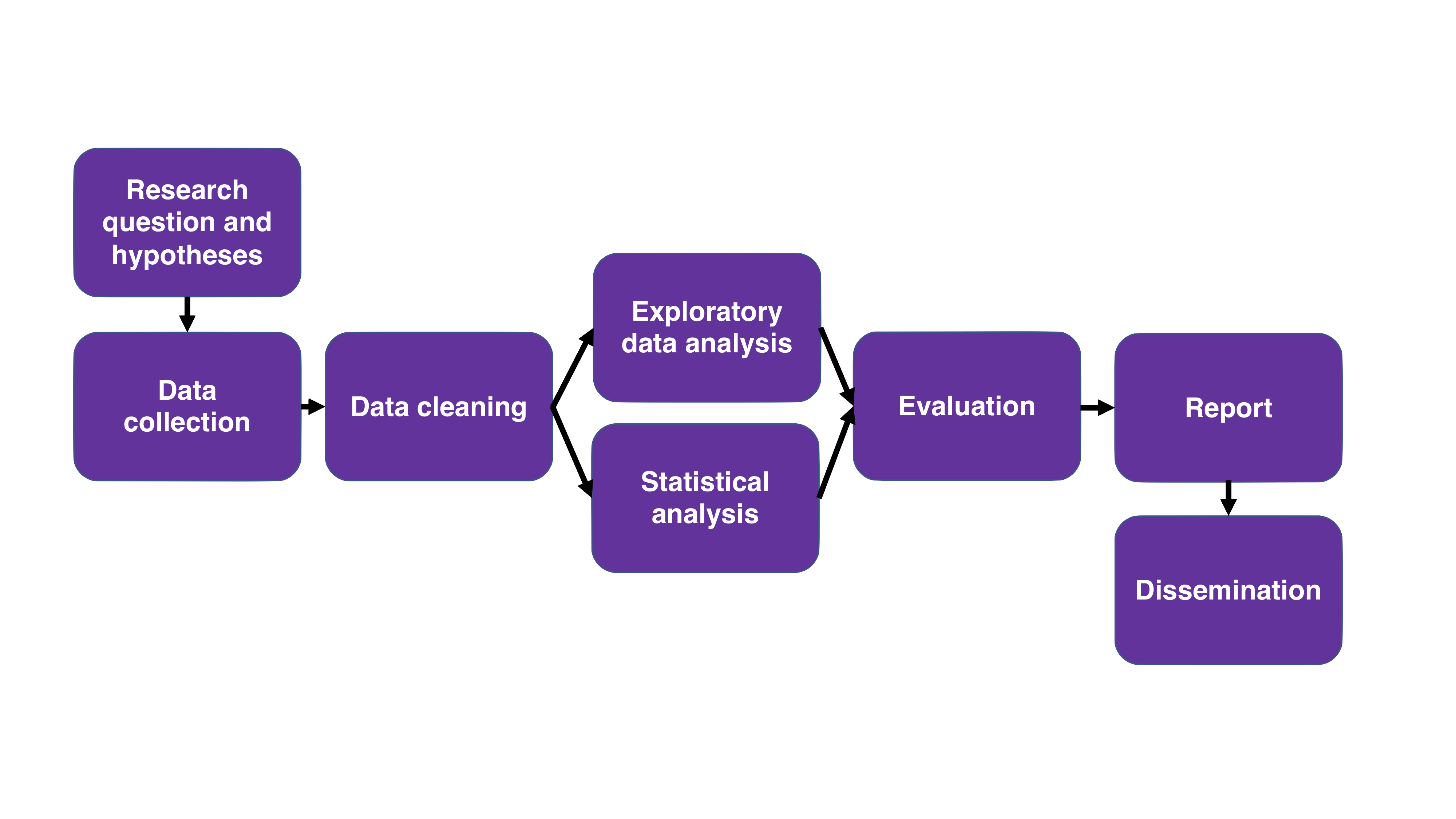

- Reproducibility is not just publishing your analysis code. The entire workflow of a research project – from formulating hypotheses to dissemination of your results – has decisions and steps that ideally should be reproducible. This extends far beyond just posting the code for your model. In particular, the data cleaning process is an important step in a research project that is often the hardest step to make reproducible, especially if you are dealing with, for example, messy text data, where it’s hard to generalize your cleaning.

Anything is better than nothing. In my presentation I talked about R Markdown, R packages, and git as example tools that help with producing reproducible research. However, these types of tools can be intimidating if you’ve never seen or used them before. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do anything. Well-documented code goes a long way for someone to be able to reproduce your research! With each new project, aim to try and improve the reproducibility of your workflow in incremental ways.

Reproducibility may not be currently valued very well in academia, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for it. It’s difficult to weigh up the benefits of being open and reproducible about your research when the current publishing and tenure systems in academia don’t necessarily compensate you for the extra effort. Indeed, some top-tier journals even discourage reproducibility, by having a no pre-print policy. However, things seem to be changing, particularly in light of the current replication crisis. A recent editorial in Demographic Research introduced a new form of article: Replications. If we encourage ourselves and our collaborators to improve reproducibility, then (maybe) this will help change the system itself.

Getting over the confidence barrier to publishing your code

On the second day of the workshop, we discussed questions from the group about open science and reproducibility. One issue raised was that people may be uncomfortable with sharing their code, because they feel it is not good enough to share.

This particular issue resonated with me because, up until relatively recently, this was how I felt. When I was still early in my PhD program, I felt uncomfortable letting other people see my code, because it didn’t seem good enough. Now, one year out of finishing the PhD, I share my code all the time, both formally (in reproducibility materials for papers and on GitHub, for example) and informally (through teaching and discussing issues with peers).

The question raised at the workshop made me think about how I made this transition. A few things come to mind that helped me:

Jumping in the deep end with projects: Like with many things, the best way to improve is often to do something that feels like it’s at the furthest reach of your ability. My confidence in code sharing increased out of necessity with my first big project, where the method and results were important beyond academia.

Formal code review: I mean ‘formal’ in a sense that you might do a pull request on GitHub and have someone else go through line by line and critique your code. I first encountered a more formal code review during the Data Science for Social Good fellowship, where I was working in a small team to produce a data and analysis pipeline. I was initially terrified of the prospect of a formal code review. My team members, a computer scientist and a software engineer, were used to designing production-level code. I, on the other hand, had only just got my head around using GitHub. But in the end it was incredibly useful, and I learnt a lot about code design.

Informal code review: Showing strangers your code is a scary prospect if you’re not used to it. But showing your PhD cohort or other peers is not so scary. Get a friend who is more comfortable with coding to look at your work and give you feedback. I learnt a lot and gained confidence through discussing and sharing code with friends during grad school.

Prioritizing improving coding skills: In the end, coding was something that I prioritized and wanted to get better at. And improving coding skills goes hand in hand with becoming more comfortable with others seeing your code. During the panel discussion, Jutta Gampe made the excellent point that we should treat code like we treat drafts of manuscripts: circulate ahead of publication, obtain feedback, and make changes.

There is no one definition of ‘good’ code: depending on the context, good code could just mean that it works, and is well documented. It doesn’t necessarily have to be the most beautiful or fastest. As quantitative social scientists, we should strive towards being proud of our data and analysis code, just like we are proud of our finished manuscripts.