The concentration and uniqueness of baby names in Australia and the US

Some great people have compiled historical data on baby names into R packages for both the US (thanks to Hadley Wickham) and Australia (thanks to the Monash group). This makes answering all manner of baby-name-related questions easy.

I was interested in looking at the distribution of baby names in these populations over time — that is, how concentrated are name choices in the most popular baby names? Is there a big difference between the number of babies that are called the most popular names compared to other names, or is the distribution more evenly spread?

The summary: names are very concentrated — the majority of babies are called a name from a relatively small subset. However, baby name concentration is declining over time, and additionally, the number of unique names is increasing.

Data

I used the used the babynames and ozbabynames packages to look at names in the US and Australia. You will need to install the Australian version from GitHub. I restricted the period to be 1960-2015 where both datasets had data. For the Australian baby names, I restricted the dataset to only include South Australia, Western Australia and New South Wales, as the other states did not have full coverage over the specified time period.1

Each dataset gives us the name, sex, year and count of number of babies. The following code loads them in and creates one tibble with both countries.

# load in the packages required

library(ozbabynames)

library(babynames)

library(tidyverse)

library(reldist)

# get the Australian and US data in one big tibble

da <- ozbabynames %>%

filter(state %in% c("New South Wales", "South Australia", "Western Australia"),

year>1959, year<2016) %>%

mutate(sex = ifelse(sex=="Female", "F", "M")) %>%

group_by(sex, year, name) %>%

summarise(count = sum(count)) %>%

arrange(sex, year, count) %>%

mutate(country = "AUS") %>%

filter(count>4) # remove weird stuff with really low counts

du <- babynames %>%

mutate(country = "USA") %>%

rename(count = n) %>%

arrange(sex, year, count) %>%

filter(count>4, year>1959, year<2016) %>%

select(-prop)

db <- da %>%

bind_rows(du)

head(db)## # A tibble: 6 x 5

## # Groups: sex, year [1]

## sex year name count country

## <chr> <dbl> <chr> <int> <chr>

## 1 F 1960 Alana 5 AUS

## 2 F 1960 Alice 5 AUS

## 3 F 1960 Antonia 5 AUS

## 4 F 1960 Beth 5 AUS

## 5 F 1960 Briony 5 AUS

## 6 F 1960 Bronwen 5 AUSNote that the US is much larger than Australia — there are around 60 times more babies in the US dataset. For example, in 2015 there were 3.7 million births in the US, compared to around 57,000 in Australia. This means the trends and patterns will be noisier for Australia.

db %>%

group_by(year, country) %>%

summarise(n = sum(count)) %>%

filter(year==2015)## # A tibble: 2 x 3

## # Groups: year [1]

## year country n

## <dbl> <chr> <int>

## 1 2015 AUS 56810

## 2 2015 USA 3688687Baby names are concentrated in a small subset of names

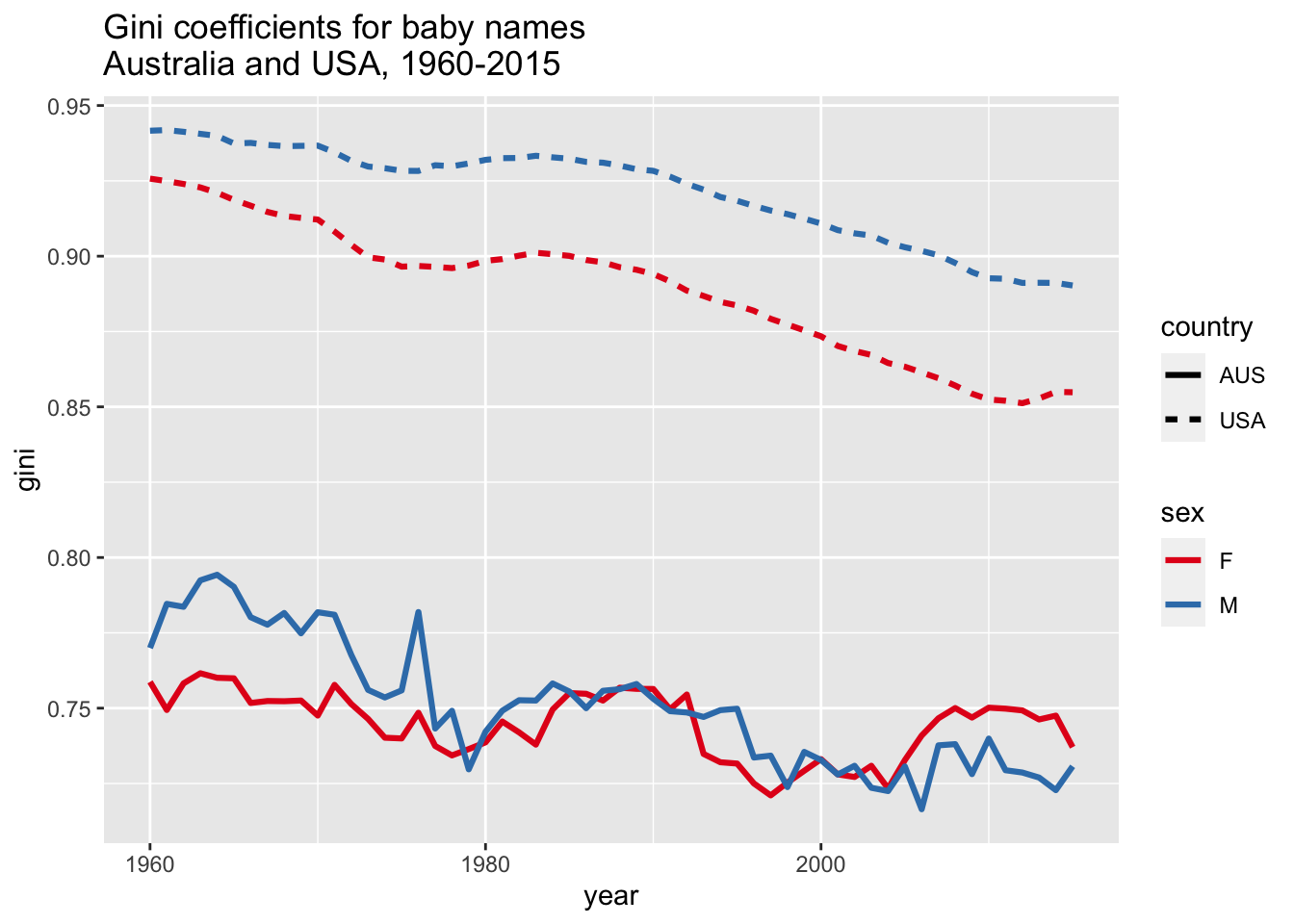

To look at the concentration of baby names, let’s calculate the Gini coefficient for each country, sex and year. The Gini coefficient measures dispersion or inequality among values of a frequency distribution. It can take any value between 0 and 1. In the case of income distributions, a Gini coefficient of 1 would mean one person has all the income. In this case, a Gini coefficient of 1 would mean that all babies have the same name. In contrast, a Gini coefficient of 0 would mean names are evenly distributed across all babies.

The plot below shows the Gini coefficients by country and sex for the period 1960-2015. We can see that, in general, the Gini coefficients are high, meaning that most babies have similar names. Concentration of names is higher in the US compared to Australia and coefficients are generally decreasing over time, particularly for the US. In the US, concentration of names is higher for boys, while in Australia, the sex difference is less clear.

db %>%

group_by(country, sex, year) %>%

summarise(gini = gini(count)) %>%

ggplot(aes(year, gini, color = sex, lty = country)) +

geom_line(lwd = 1.1) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

ggtitle("Gini coefficients for baby names \nAustralia and USA, 1960-2015")

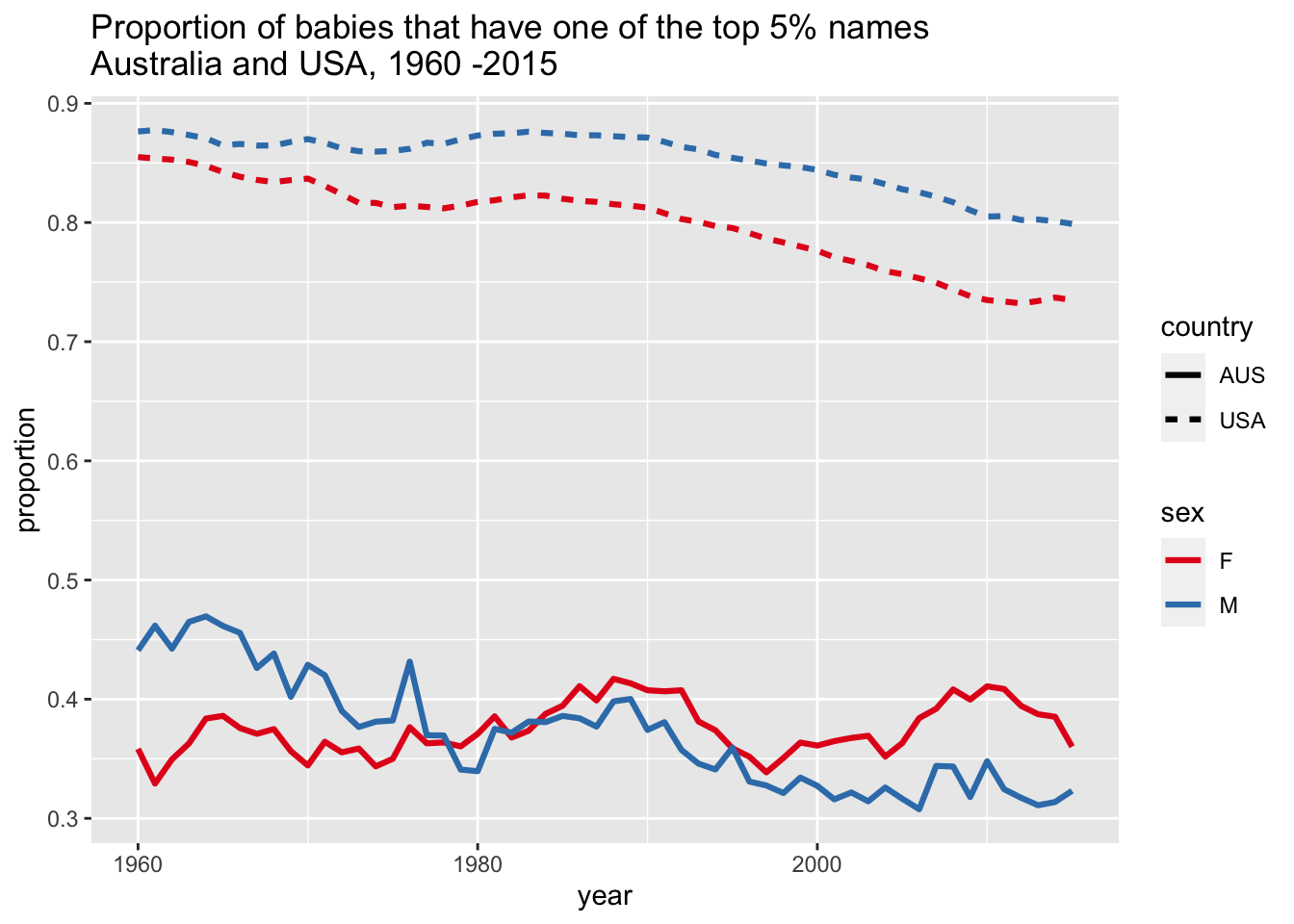

We can plot this concentration a different way: let’s look at the proportion of babies who have a name in the top 5% most popular names.2

Note that the trends and patterns are pretty much identical to those above. The levels are quite high: in 1960 in the US, almost 90% of all babies born were called a name that was in the top 5% most popular names (note that this corresponds to the around the 250 most popular names).

db %>%

group_by(sex, year, country) %>%

mutate(id = row_number()-1,

cumul_count = cumsum(count)/max(cumsum(count))) %>% # get cumulative proportion of babies with each name

mutate(rank = ntile(id, 20)) %>% # find the top 5th percentile

filter(rank==20) %>%

slice(1) %>%

ggplot(aes(year, 1-cumul_count, color = sex, lty = country)) +

geom_line(lwd = 1.1) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

ylab("proportion") +

ggtitle("Proportion of babies that have one of the top 5% names \nAustralia and USA, 1960 -2015")

Names are getting more unique

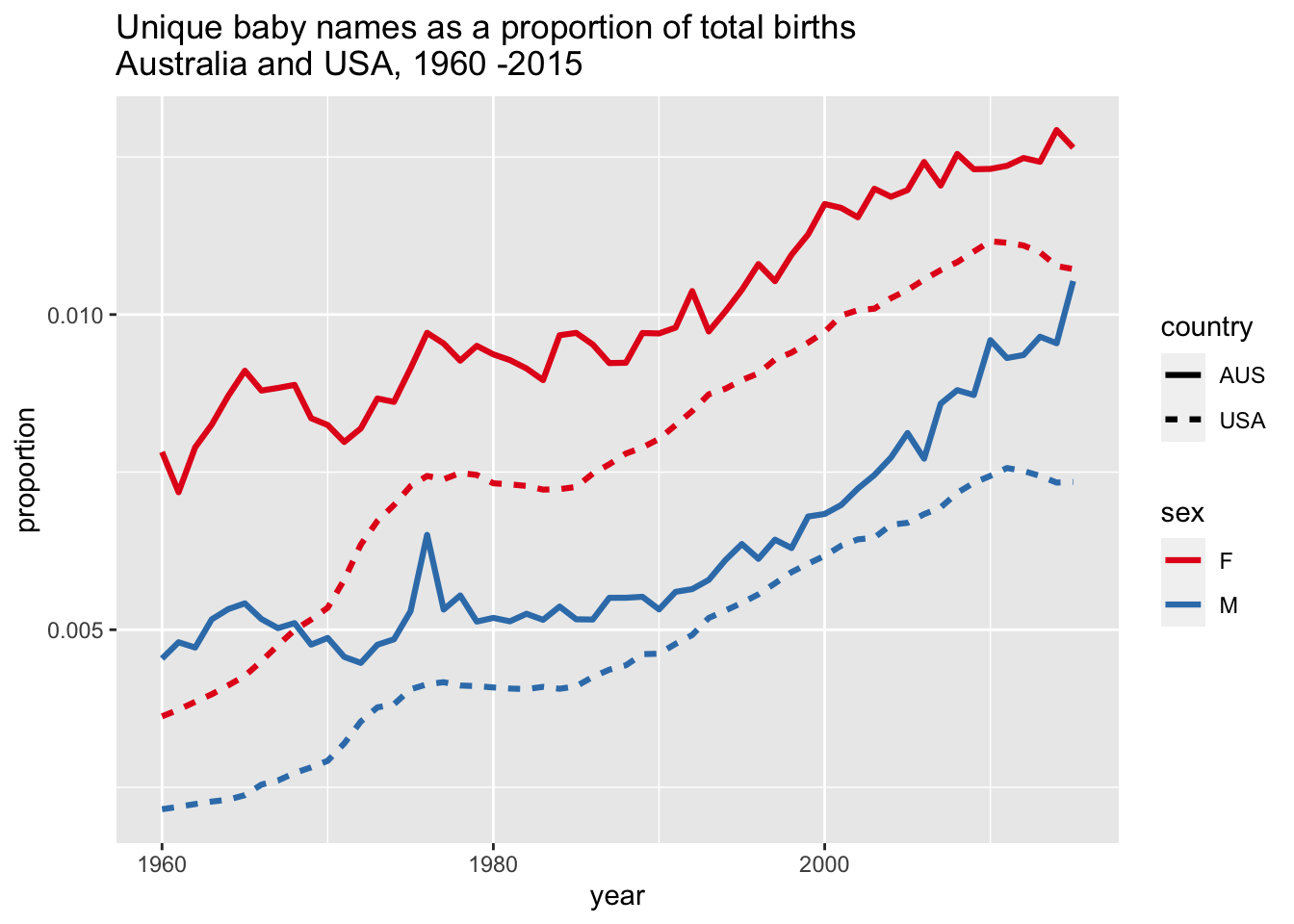

Is the distribution of baby names become less concentrated because there are more unique names being used over time, or just because people are opting to choose less popular but already existing names?

It seems that there is an increase in unique names being used over time in both countries. However, there has been a slight decrease in uniqueness in the US since 2010. (Perhaps people are finally running out of alternative ways of spelling ‘Jackson’.) Interestingly, the number of unique girls names is higher as a proportion of total births compared to boys. This is consistent with the observation above that Gini coefficients are higher for boys.

db %>%

group_by(sex, year, country) %>%

summarise(prop_uniq = n()/sum(count)) %>%

ggplot(aes(year, prop_uniq, color = sex, lty = country)) +

geom_line(lwd = 1.1) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

ylab("proportion") +

ggtitle("Unique baby names as a proportion of total births \nAustralia and USA, 1960 -2015")

Summary notes

People tend to choose a baby name from a relatively small subset of popular names, although name uniqueness is increasing slightly over time. Concentration of baby names is generally higher for boys, and higher in the US compared to Australia. So even though there are many more interesting sounding names in the US, a larger proportion of the population just stick to the more usual names.

Changes in popular baby names and how people choose to name their baby are influenced by underlying social processes, such as era-specific events, country-specific cultural norms, and fertility intentions. Sociologists and demographers such as Phillip Cohen and Josh Goldstein have done some interesting work in this area.